REAL Tests of the 157″ AWALL MicroLED TV – Results Are In!

January 30, 2026Is MicroLED really the ultimate technology for massive TV screens? It’s really hard to know because despite being prominently displayed at every TV manufacturer’s booth at CES, there’s a surprisingly small amount of real-world testing on them. So, I decided to buy one, specifically a 157” wide screen 0.9-pixel pitch MicroLED screen from AWALL, and I’m going to break this video into three sections. First, I’ll go over the technology and explain the key differences, both good and bad between MicroLED and more common display tech like LCD and OLED. Then, I’ll go over the installation process, the setup, and calibration experience that I went through. Last, I’ll test the actual brightness, contrast, color gamut coverage, power draw, and input lag and compare those to AWALL’s marketing claims.

But before any of that, while we’re on the subject of marketing, I want to talk about AWALL’s headline advertisement that says Big Screen, Small Price.

Starting with the obvious, is it a big screen? Absolutely, and MicroLED is currently the only way to get a direct view screen bigger than 116”. To put things into perspective, this is a 65” screen, which is the most common screen size in the US in 2026. Then we’ll step up to an 85” screen, which at one point was considered huge and is 70% larger in terms of screen area than a 65” screen. Here’s a 97” screen, which is currently the largest OLED you can buy and will run you around $25,000 for LG’s version. Here’s a 116” screen, which is the largest available LCD based screen, specifically found in the $20,000 Hisense 116UX. At CES 2026, Samsung recently announced they’ll be making a 130” LCD based TV sometime in 2026 and here’s what that would look like. No official pricing is available but I’m guessing it will have a price tag somewhere around $40,000-$50,000.

In contrast, my screen from AWALL is not directly comparable due to its custom aspect ratio, but when viewing 16:9 content it’s equal to a 135” screen with letterboxes on each side, and when watching a movie with a typical 2.39:1 aspect ratio it is equivalent to a 162” 16:9 screen. So yeah, it’s big.

But let’s be honest, the second part of their claim, Small Price, doesn’t track. This 157” screen with 0.9-pixel pitch runs somewhere around $50,000-$55,000 depending on promotions. But to be fair, AWALL does have a point that their $55,000 MicroLED option is significantly lower priced than the options from Samsung, LG, and Hisense that still cost between $200,000 and $300,000. So, with that out of the way, let’s talk about the basics of MicroLED TV technology.

First, all MicroLED TVs regardless of brand are modular. AWALL is specifically built with 27” diagonal cabinets so you can arrange them pretty much however you want to get custom screen sizes to fit your exact space and viewing habits as long as you can make it from some combination of 27” diagonal screens. My specific screen is six panels wide and five panels tall.

However, unlike LCD TVs and OLEDs that have varying pixel size and pitch so that a 50” screen and a 116” screen both have the same 4K resolution, the pixel pitch on a MicroLED is the biggest contributor to its cost. At 0.9 pitch, each 27” cabinet has a resolution of 640 pixels wide and 360 pixels tall and that means to get a true 4K 16:9 screen, you’d need six panels wide and six panels tall. If you went with the less expensive 1.2-pixel pitch, each 27” panel is 480×270, so you’d need an 8×8 screen to get 4K resolution.

That said, the general rule for pixel density is that if you multiply the pixel pitch by 10, that will give you the viewing distance in feet where individual pixels are indistinguishable. So, for 0.9-pixel pitch, anyone sitting 9 feet back or further wouldn’t be able to see pixelation even with perfect vision. The same would be true for 1.2-pixel pitch for a person sitting 12 feet back.

In practice, as someone who spends a lot of time critically watching screens and nitpicking every minute detail, the resolution and pixel pitch are a complete non-issue on this screen, even though 16:9 content is displayed at 3200×1800 which is 83% of true 4K which would be 3840×2160. But because my specific screen size is still six panels wide, I do get the full 3840×1600 resolution for widescreen content, which is the same that a 16:9 full 4K screen would produce, but my screen just has thinner black bars at the top and bottom.

The second unique part of a MicroLED screen is that each of the 27” cabinets is just a housing for the power supply and controller board, and the screen itself is made up of magnetic LED panels. Each cabinet has eight of those panels, each with a resolution of 160×180 and each pixel is made of separate red, green and blue LEDs for a total of 86,400 LEDs per little magnetic square, and there are just under 700,000 LEDs per 27” cabinet.

From a logistics standpoint, MicroLED has a huge advantage over extremely large TVs because they can be transported and installed piece by piece rather than needing to maneuver an entire 12 feet wide by 6 feet tall TV into your living room. From a durability and serviceability standpoint, if a panel were to get damaged the entire process of replacing it and recalibrating it can be done in less than five minutes with just a suction cup tool and replacing power supplies and controller boards is equally trivial. It’s for these reasons that MicroLED is extremely common for trade shows and concerts where displays need to be constantly broken down, transported, and relocated.

However, the obvious downside of modularity is that instead of a single uniform smooth glass screen, you get a screen that’s actually made up of 240 small squares and getting all of them perfectly aligned and leveled so that there are no borders between them is quite a process. To be totally honest, I haven’t gotten mine as perfect as the ones I’ve seen at CES where you can stand a few inches from the screen and not see any seams, but from my normal seating position roughly 10 feet from the screen the seams are not visible.

From a performance standpoint, MicroLED is also fundamentally different than other direct view TV technologies. LCD TVs including QDLED, Neo QLED, MiniLED, and most recently RGB MiniLED use a color LCD panel to create an image and then shine a backlight with LEDs through that front LCD panel to illuminate it. And while LCD technology has come a long way in the last five years due to advances in the number of local dimming backlight zones, the big issue is that if there is a small bright area on a mostly dark screen, the entire dimming zone needs to be lit in order to illuminate that one bright spot and the rest of the dimming zone that is supposed to be black will also get illuminated, which is called blooming.

OLED on the other hand, which includes QD-OLED and W-RGB OLED are self-emissive, meaning each pixel creates its own light and doesn’t need a backlight. So, when an OLED has a few bright pixels in a dark space, it won’t need to illuminate the surrounding black pixels, which is why OLED is typically considered king in terms of black levels and contrast.

But MicroLED is also a self-emissive display. So, there’s no backlighting to cause blooming and a fully lit white pixel can have a completely black pixel right next to it with no blooming and very little fringing. But a major advantage of MicroLED over OLED is that unlike the organic LED compounds used to make OLEDs, the inorganic LEDs in MicroLED aren’t prone to burn in. The other unique aspect is that each LED isn’t covered with a sheet of glass like on an LCD or OLED, but instead the surface of each small MicroLED panel is much thinner which in my experience creates less of the haloing that even an OLED can have around white text on a black background. But the biggest advantage of the MicroLED coating over plain glass is the fact that a MicroLED panel has almost no glare, so you can watch with the windows wide open and the lights on without significant degradation in picture quality.

So, with all the potential advantages of MicroLED, why isn’t it more common in residential installs?

First, as we’ve already gone over, MicroLED screen resolution is based on size and at 0.9-pixel pitch you’ll need a 3×3 cabinet 81” diagonal screen just to get 1080p resolution. So, to make use of the tech you need to have a wall that can fit a really big screen.

Second, economy of scale is the only reason that you can buy an 85” TV for $600, and the relatively low production scale of MicroLED means that each panel costs more to produce. If MicroLED becomes common place you can expect prices to plumet, but for now the individual parts are relatively expensive compared to LCD and OLED.

Third, even though AWALL is selling these for residential use, they still feel very much like a commercial product and buying and installing it isn’t like bringing home a TV from Best Buy in the back of your SUV.

That brings me to the installation process and my experiences so far with my screen.

Assuming you’re going to tackle the installation yourself, before your MicroLED screen arrives you’ll need to do some significant preparation. For power, my 157” required three power drops behind the screen on a dedicated 15A circuit, and a total of 18 Cat6 Ethernet drops run to a separate room to house the controller.

Once that was done, according to AWALLS specifications I cut three sheets of furniture grade ¾” birch plywood to custom size and mounted them to the studs so that each cabinet would have a secure mounting point.

Next, each cabinet is lined up and secured together using a fairly easy to use connection system so that the seams are perfectly aligned, the power and data runs are routed through the cabinets, and then the magnetic LED panels are installed and leveled, which is probably the most important and time-consuming aspect of the entire build. Depending on your level of perfectionism, you could spend days making micro adjustments to the magnets to make the seams between the panels completely invisible.

Once you have the physical screen in place, you end up with something like this that sits around 2 inches off of the wall, which is ¾” of plywood and 1.25” of screen. My screen will eventually be surrounded in wood slats that will make it closer to flush mounted and will hide the power outlets and speaker wires, but I haven’t gotten to that point yet.

Once the screen is fully assembled, the last step is to configure the controller to know exactly where each panel is located on the screen. Once you’ve got that mapped out the TV is ready to display content, sort of.

That brings me to maybe the main reason MicroLED displays aren’t more common for residential use, and that’s that they’re just displays, more similar to a computer monitor, and not a TV. If you’re used to a TV with a remote, speakers, smart apps, or even a power button, it doesn’t have any of those things. I would guess that the vast majority of AWALL installs, and MicroLED installs in general, are being done by professional home theater installers and are being paired with $50,000-$100,000s of extra equipment for automation through Savant or Control4, custom audio solutions, high-end video sources like Kaleidescape and signal processors like MadVR. So, for me as a more DIY type, with a little tighter budget if you can even call it that and being a big fan of open-source automation like Home Assistant, instead of proprietary dealer systems like Control4, there was quite a bit of figuring out to do.

Starting with the most interesting part, the power button, because there’s no remote and the LED controller, which in my case is a NovaStar MX40, has a power button on the front of it, but turning that off doesn’t actually turn off the LED wall. Even with zero pixels lit, the 157” AWALL consumes around 650 watts all the time, which is twice as much as my 100” Hisense U76N uses on max brightness. So, when you’re not watching your MicroLED TV, you should definitely cut the power to the screen completely which I did using a Shelly 1PM Smart Relay and Home Assistant that watches my Sofabaton X1 remote’s current activity.

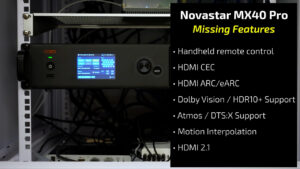

Next, the NovaStar MX40 has three HDMI inputs and one Display port, but the only audio output is optical. So, without ARC or eARC that means no Dolby Atmos or advanced DTS audio. For that, you’re going to need something else earlier in the chain to pull out the audio if you want more advanced formats.

The MX40 also lacks advanced HDR video formats like Dolby Vision and HDR10+. So again, if you want to use those, you’re going to need some other processor earlier in the chain to accept those formats and then output them into HDR10 or HLG for the NovaStar.

I solved both of those problems using an HDFury VRROOM which is a $600 HDMI splitter, matrix, audio extractor, and signal processor that can do all kinds of crazy things if you know how to use it and are willing to spend some time on setup. Honestly, I’m not sure how a purely Home Assistant based automation setup could work without the VRROOM, so it’s pretty much a must have in my book.

But even then, you’ll also need a universal remote to tie everything together, and I’m using a Sofabaton X1 that I had sitting around collecting dust, but a more advanced remote like the new X2 or Unfolded Circle would be much better. That means just to get all the base level features of a normal TV like a power button, volume control, and input switching you’re probably going to spend at least an additional $1000-$1500. Depending on what you want to do you could easily spend $10,000 or more, and you’ll also need a fair amount of knowledge about audio and video signals and processing, automations, and APIs. Or, as I said, you could just pay someone to give you a turnkey solution, which I think is what most people end up doing.

However, some of the headache of using a controller like the NovaStar MX40 also comes with benefits that you don’t get with a TV. Specifically, the NovaStar controller is very powerful in terms of scaling and layering, so you can put up to four different inputs on the screen at the same time in any arrangement and size combination that you want. I’ve personally set up a multi view that has four equal sized Fire TV sticks, one that has a single large 4K input, and four 1080p inputs, and separate setups for 16:9, IMAX, and true 2.40:1 cinemascope content. The NovaStar lets you set up each of these layouts as a preset that you can then recall using the web API, so in Home Assistant I have some automations that watch for activity changes on the Sofabaton remote control and then call the specific preset for that activity using Node Red and the NovaStar web API. The overall solution ended up being surprisingly simple and robust considering it’s orchestrating ten devices from five different manufacturers, but that’s the magic of Home Assistant.

So, the last remaining question is whether the performance matches the expense. And that means it’s time to break out the meters.

Starting with brightness, measuring peak brightness with Calman Ultimate using a C6 Colorimeter on a 25% window, the AWALL comes out between 805 and 820 nits. While an LCD based TV like the $30,000 Hisense 116UX can put out insane peak brightness numbers close to 7000 nits on a small 1% window by concentrating all its power into a single backlight zone, the AWALL has a separate power supply for each of the 27” cabinets, so peak brightness remains consistent no matter the window size and still measures 840 nits even with a full screen pattern.

However, AWALL does list peak brightness at 1200 nits, not 800, but to get that you have to go into the LED controller and select enable overdrive, which then lets you increase the brightness to a max of 144.6%, and doing that does get very close to 1200 nits. But for as much as I paid for this TV, I’m not going to do anything that could potentially lower the lifespan of the LEDs. And to be totally honest, 800 nits is already an insane amount of brightness that looks great even in a room with windows open and lights on, and at night with the lights off 800 nits is WAY too bright and I end up turning the brightness down to 30%, which is still around 250 nits.

If you’re normally a projector person, to put these brightness values into perspective, even on a white 1.1 gain screen a projector would need to have around 17,000 lumens after calibration to create the same size screen and put out 800 nits, and that’s on a white screen, which is important to keep in mind.

Because the real kicker is contrast. AWALL claims a 15,000:1 contrast ratio, but I’m not sure where that number comes from because with a maximum brightness of 807 nits and a minimum brightness of zero the contrast ratio is basically infinite. Even with the specialized contrast pattern that I use to prevent dimming tricks on projectors, the AWALL has that same basically infinite contrast ratio due to the self-emissive technology, and these are similar results to what you’d see with an OLED which is also self-emissive. But MicroLED seems to be a little bit better at handling near-black values and OLED tends to have a slightly higher minimum brightness and the step from “all the way black” to “almost all the way black” is actually pretty large, which can be very noticeable in a dark room.

If you’re comparing a MicroLED to a projector the biggest advantage is bright room performance. As I said, the only other way to get a screen this large is with a projector, and the problem with a projection is that the color of the screen when the projector is off is as dark as the black level can ever be. With the lights on and windows open, the AWALL still has a black floor of just 6.6 nits, and if we compare that to a 1.0 gain projector screen sample in the same lighting, that measures 177.4 nits, and that means that for a projector to have similar bright room performance of 800 peak nits and a 6.6 nit black floor you’d need to pair a 0.04 gain screen which doesn’t exist with a 455,000 lumen projector, which again, doesn’t exist. Even a 0.6 gain lenticular ambient light rejecting screen measured 41.9 nits in that same environment, which corresponds to 77% ambient light rejection, but it still had a black floor that was over six times higher than the AWALL and to hit 800 nits of peak brightness you’d need to pair it with a 30,000 lumen projector. So specifically for bright room performance, the AWALL is basically unbeatable in today’s market.

In terms of color performance, the AWALL also performed very well covering just under 89% of the widest BT.2020 HDR color space, and 99% of P3, which is the color space that most HDR content is mastered in.

In terms of color accuracy, the color temperature was as close to D65 as I’ve ever seen and tracked perfectly in terms of Luminance and EOTF without any calibration. In Calman Ultimate’s color checker, the AWALL had an average color error of 1.8 and almost all colors measured below the delta error threshold of 3, which is where the human eye can no longer tell the difference between two colors.

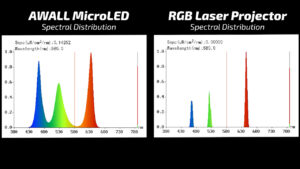

I also measured the spectral distribution of the LEDS and as expected, each color has a much wider distribution than you would find on a triple laser projector, which will help prevent a phenomenon called metamerism where different people can perceive the colors on a screen differently based on slight differences in the color sensing cone cells in their eyes.

Next, I tested the gaming input lag on the AWALL, and like most projectors and TVs you need to play with settings to get the lowest possible input lag. The NovaStar controller has settings that introduce either 0, 1, or 2 frames of additional input lag, but the minimum system wide input lag seems to be 2 frames or around 34 ms, which is pretty disappointing.

So, to get the AWALL’s best gaming performance, which is 33.6 ms of input lag, the controller has to be in “send only” mode, which outputs the resolution mapped 1:1 on the display with no scaling and no processing. Even though that’s not under the 20 ms of input lag that I usually recommend for a gaming-focused setup, 33.6 ms is still more than acceptable for casual enjoying video games.

Unfortunately, on my specific system I can’t use send only mode because 4K content needs to be scaled down to fit the height of my screen and 1080p content needs to be scaled up, so the only way I could game in this mode would be to use a PC with a custom resolution of 3840×1800.

That means I’m stuck using scaling and the NovaStar needs to be put into “All In One” mode, which introduces an additional frame of input lag and brings the total input lag to 52.2 ms, which is right on the cusp of where I can start to “feel” the lag. But unlike most projectors where the game specific modes maintain very similar overall performance, the low lag setting on the NovaStar causes pretty consistent glitching, and I wouldn’t really consider it usable. So, the actual input lag that most people can expect is 4 full frames or around 78 ms. While that’s still under the 100 ms threshold where you absolutely can’t game on a screen, 78 ms is still pretty bad by today’s standards.

Last, the strangest and craziest thing about the AWALL is its power draw, especially because AWALL specifically calls out lower power consumption on their advertisements. But I guess it’s all about “lower than what,” because at 100% brightness the screen itself pulls between 900W to 1200W and the NovaStar controller uses around 72W, so that means you can expect an average of around 1kWh of consumption every hour that the TV is on, which is high. But let’s be honest, if you can’t afford 20 cents an hour to watch your TV, you’re probably not buying a $50,000 TV in the first place.

However, the strangest part to me is that reducing the brightness to 30% has almost no effect on power consumption and the TV still draws 970 watts at 1/3 output. Even more ridiculously, when the panels are powered on but are completely black with no signal coming from the NovaStar, they are still drawing a steady 680 watts in standby mode which is nuts and ultimately means the MicroLEDs themselves are only drawing 300-500 watts and the rest is power supply loses and controller boards.

For comparison, my 100” Hisense U76N draws an absolute maximum of 300 watts, and while the AWALL has over 2.5x the screen area of the 100” TV, that would still only account for 750 watts, so there’s clearly some room for improvement in terms of efficiency.

Looking just at the numbers there’s no doubt that the AWALL has pretty unbelievable performance, but in terms of watching actual content, I’ve reviewed hundreds of projectors and been in theater rooms that cost many hundreds of thousands of dollars with black velvet walls and $75,000 projectors, and this MicroLED screen in my mostly unfinished living room with white walls and ceiling still absolutely blew me away.

There’s just nothing else like it because OLEDs can’t get anywhere near as big, and projectors can’t reasonably be bright enough to perform similarly in a bright room, and the color, contrast, and brightness of the AWALL is really something you have to see to believe.

However I think for AWALL to get true consumer level adoption outside of mega mansions, sports bars, and the occasional hardcore early adopter enthusiast, it really needs a different LED controller that’s designed less for the commercial and broadcast space and more for home theater use with things like lower input lag, Dolby Vision, eARC, HDMI CEC, a remote, and a power button. I hope when one of those is available, I’ll be able to just swap out my controller and still use the same LED wall.

If you’re familiar with my channel you know I don’t generally make single product reviews, but this was enough of an investment for me to want to squeeze two videos out of it and frankly I also needed the extra time to get everything set up and automated to the point where someone could watch TV without a 100 page instruction manual. However, coming up in two weeks I’m going to put the AWALL up against some absolute light cannon projectors with the latest tech in ambient light screens to see what a similar setup would look like using a projector instead of MicroLED.

As always there are no sponsored reviews on this channel. Again, I’m not telling you to take out a second mortgage to buy a giant TV but if this looks like something you’re interested in I’ve got an affiliate link and all of AWALLs information below and if you mention that you heard about AWALL from this video I promise they’ll treat you extra nice and I’ll get a little referral commission at no cost to you, which I’d very much appreciate.

I’d also like to thank all of my awesome patrons over at Patreon for their continued support of my channel, and if you’re interested in supporting my channel please check out the links below. If you enjoyed this video, please consider subscribing to my YouTube channel and as always, thanks for watching The Hook Up.

Buy the AWALL (affiliate link)

Other stuff in the video

HDFury VRROOM

SofaBaton X1

Shelly 1PM Gen4